Most AI guides teach you tools. They're organized by category: chat interfaces here, research tools there, coding assistants over here. Ten levels of apps to master.

That's useful if you're learning the landscape. But it's the wrong frame if you're trying to actually work with AI.

I've been building with Claude daily for two years. Across strategy, content, software, and business operations. What I've learned isn't about which tools to use. It's about a progression, four levels that determine whether AI remains a novelty or becomes a force multiplier.

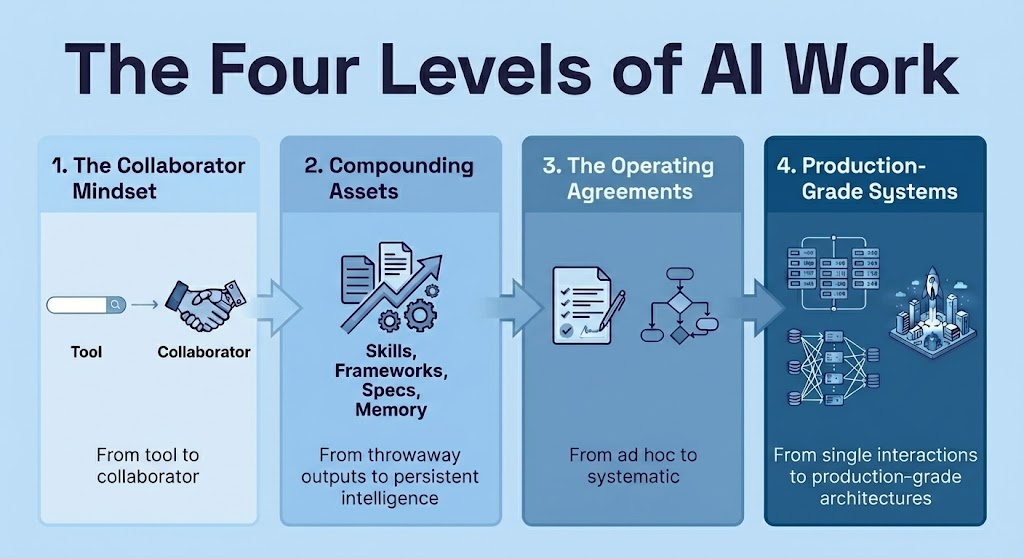

The progression looks like this:

- Level 1: The Collaborator Mindset, from tool to collaborator

- Level 2: Compounding Assets, from throwaway outputs to persistent intelligence

- Level 3: The Operating Agreements, from ad hoc to systematic

- Level 4: Production-Grade Systems, from single interactions to production-grade work

Each level unlocks capabilities the previous levels can't reach. And each level requires the ones before it, you can't skip ahead.

Most people stay at Level 1, asking “which AI app should I use?” and wondering why they get inconsistent results. The people transforming their work have found their way to Level 4, building systems that get more powerful over time.

Here's the path.

Level 1: The Collaborator Mindset

From tool to collaborator.

Most people use AI like a search engine with better sentences. They ask a question, get an answer, move on. That's Level 1, and most people never leave it.

You can spot Level 1 thinking by the questions people ask: “What's the best AI for writing?” “Should I use ChatGPT or Claude?” “What prompt should I use for this?” These are tool questions. They assume AI is something you pick up, use, and put down.

The shift that changes everything: treating AI as a collaborator in a system, not a tool you query.

Here's what I mean. I was building a content engine, trying to figure out what technical specifications I needed. Gap analysis after gap analysis. What data schemas? What validation rules? What handoff protocols?

Then I realized I was asking the wrong question. I was asking “what software specifications do I need?” when I should have been asking “what operating agreements do Claude and I need?”

When Claude is the system, most technical specifications dissolve. Data contracts between stages? Claude interprets meaning from files directly, no JSON schemas needed. Template logic? The markdown files describing each stage are the generation logic. Quality gates? Claude evaluates, I review. The collaboration is the system.

What remains are questions about how we work together: Who decides what when? What persists versus what gets re-derived? When does Claude stop for input versus proceed autonomously?

This isn't a semantic distinction. It changes what you build and how you build it. Tool thinking produces prompts. Collaborator thinking produces systems.

That reframe, from tool to thinking partner, is the foundation everything else builds on.

You're at Level 1 when you're still asking “which AI app should I use for this?”

You advance to Level 2 when you start asking “how do I build something that lasts?”

The takeaway: The question isn't which tool to use. It's what kind of working relationship to build.

Level 2: Compounding Assets

From throwaway outputs to persistent intelligence.

Once you see AI as a collaborator, you notice something: most AI usage produces throwaway outputs. You ask, you get an answer, it disappears into conversation history. Nothing accumulates. Every session starts from zero.

This is like having a brilliant colleague who gets amnesia every night. Every morning you explain everything again. Every project starts from scratch. The collaboration never deepens.

Level 2 is building assets that make every future session more powerful than the last.

Skills. Claude can learn reusable instructions. I've built skills for competitive intelligence, for content creation, for prospect research. Each one encodes expertise that used to live only in my head. Now it's externalized, repeatable, improvable. When I return to a task months later, the skill is waiting. I don't re-explain my methodology. I don't re-teach my preferences. The skill contains them.

Frameworks. Not prompts, systems. My content pipeline has a stage file for each phase, and a separate framework file containing the actual tools for that stage. Eleven insight prompts. Thirteen headline formulas. Eight messaging frameworks. Eleven psychological triggers. These aren't suggestions Claude considers. They're structured methodologies Claude loads and follows.

Specifications. Strategy documents that become implementation guides. I don't just plan in Claude and then go build elsewhere. I create detailed specs, architecture diagrams, success criteria, implementation phases, and hand those specs to Claude Code for autonomous implementation. The spec becomes the source of truth, not a throwaway planning document.

Memory. Context that carries across sessions. Past decisions, past patterns, past preferences. When I return to a project after a week, Claude already knows what we were building and why. I don't re-establish context. I continue where we left off.

The architecture matters here. Take my content frameworks: each stage has two files. A stage file defines the process, what happens, in what order, what the inputs and outputs are. A framework file contains the actual tools, the specific prompts, formulas, or triggers for that stage.

Why separate them? Extensibility. Want to add a twelfth insight prompt? Add it to the framework file. The stage logic doesn't change. Want to experiment with different psychological triggers? Swap the framework file. The process stays stable while the components evolve. This is software architecture thinking applied to AI collaboration.

This is what compounding looks like. Every framework I build makes future work faster. Every skill I create means I never solve that problem from scratch again. Every specification becomes a template for the next project. Session 100 is dramatically more powerful than session 1, not because I've gotten better at prompting, but because I've built infrastructure.

You're at Level 2 when you have reusable assets, skills, frameworks, specifications, that persist across sessions and make future work faster.

You advance to Level 3 when you realize these assets need agreements about how they're used.

The takeaway: The people getting the most from AI aren't the ones with clever prompts. They're the ones building assets that compound.

Level 3: The Operating Agreements

From ad hoc to systematic.

Here's what nobody talks about: the agreement between you and AI about how you work together.

Not prompts. Not tools. The meta-level understanding of roles, responsibilities, and boundaries.

Think about how you'd onboard a talented new team member. You wouldn't just hand them tasks. You'd explain how decisions get made. What authority they have. When to check in versus proceed. What “good” looks like. You'd establish norms before diving into work.

AI needs the same thing. Without explicit agreements, you're collaborating with someone who doesn't know the rules, and you'll get inconsistent results because the rules change with every conversation.

Decision authority. Claude proposes, I decide, on strategy, on voice, on anything requiring judgment about my business or audience. Claude executes autonomously on implementation details within defined parameters. This isn't about trust. It's about appropriate division of labor. Some decisions require human judgment. Others don't. Be explicit about which is which.

Human-in-the-loop pause points. Some stages require me. In my content pipeline, Stage 5 is Personalize. The system pauses. It needs something only I can provide: my specific stories, my client examples, my experiences. This isn't a formality, it's the stage where the article becomes something I actually wrote, not something anyone with the same frameworks could have produced. Know where the human must enter, and design the pause into the system.

Visible reasoning. When Claude makes decisions, I need to see the thinking. In Stage 0 of my content pipeline, I give Claude seven audience segments and ask it to score a topic against each one. It returns a matrix with fit scores and reasoning for each. I can see the analysis. I can challenge it. “Why did Segment 3 score higher than Segment 5?” The intelligence is visible, not hidden in a black box. If you can't see the reasoning, you can't improve the system.

Escalation triggers. When does Claude stop and ask versus proceed? Low confidence. Conflicting requirements. Anything touching brand voice or public positioning. Anything involving commitments to real people. The goal is autonomy within bounds, not constant checking, but the bounds must be explicit.

Quality standards. What does “done” look like? Specific checklists. Red flag scans for AI-sounding language. Voice validation against documented patterns. Word count ranges. Structure requirements. Make standards explicit so evaluation isn't subjective. “Good enough” isn't a standard. A checklist is.

Persistence rules. What must be stored versus what can be re-derived? My voice profile persists. The frameworks persist. Past decisions about brand positioning persist. Specific article drafts can be regenerated. Know what needs continuity and what's disposable.

Most people never define these agreements. They interact with AI ad hoc, getting inconsistent results, wondering why it works sometimes and not others. The answer is usually that the operating agreement was implicit and shifting.

You're at Level 3 when you have explicit agreements, written down, about how you and AI work together.

You advance to Level 4 when you're ready to build sophisticated systems on top of this foundation.

The takeaway: Define the operating agreement. Write it down. This is what separates people who use AI from people who work with AI.

Level 4: Production-Grade Systems

From single interactions to production-grade architectures.

With the right mental model, compounding assets, and clear operating agreements, you can build things that weren't possible before. Level 4 is where AI work starts to look like engineering, systems with multiple components, clear interfaces, and emergent capabilities.

Here's what Level 4 looks like in practice.

A Content Pipeline with Extensible Frameworks

My 7-stage content system isn't a prompt. It's an architecture with clear interfaces between stages and swappable components within each stage.

Stage 0 is Audience. I give Claude my seven segments, it scores the topic against each with visible reasoning, a matrix showing fit scores and the logic behind each score. I review the analysis, challenge where needed (“Why did Segment 3 score higher than Segment 5?”), and lock the target segment. This isn't AI making decisions for me. It's AI showing its work so I can make better decisions.

Stage 1 is Ideation. The framework file contains eleven insight prompts, Belief Archaeology, Contrarian's Truth, Failure Autopsy, Pattern Recognition. Each produces a different type of original thinking. Claude doesn't pick randomly. It evaluates which prompt fits the topic and audience, explains why, and shows alternatives I might consider.

Stage 2 is Hook. Thirteen headline formulas based on how attention actually works. Claude evaluates which serves the insight from Stage 1, demonstrates the reasoning, proposes options with tradeoffs.

Stage 3 is Architecture. Ten content structures. Eight messaging frameworks. Story shapes mapped to argument types. All in separate files, all loadable based on what the piece needs.

Stage 4 is Draft. Eleven psychological triggers deployed intentionally, Biology is King, Breaking False Beliefs, Identity Consistency. Claude identifies which triggers serve this specific piece and explains the deployment plan before writing a word.

Stage 5 is Personalize. Human-in-the-loop pause. The system needs my specific stories, my examples, my voice. This is where generic becomes mine. The stage is designed to stop and wait for what only I can provide.

Stage 6 is Polish. Red flag detection against a specific checklist of AI-sounding phrases. Voice profile validation against my documented patterns. Quality gates with explicit pass/fail criteria.

The power is extensibility. Each stage has a process file and a framework file. Add a new messaging framework? Add a file. Experiment with different triggers? Swap the framework file. The architecture stays stable while the components evolve. I can improve any stage without redesigning the system.

A Multi-Agent Architecture for Voice Interviews

I'm building Interview Studio using Jido, an Elixir framework for autonomous agents. The architecture looks like a TV production studio, multiple specialists working simultaneously, each focused on their role, all contributing to a single coherent output.

The Director owns the conversation. It's the only voice the user hears. It decides what to ask, when to probe deeper, when to transition to a new topic. It synthesizes input from the other agents but makes the final call.

The Analyst watches the same conversation, extracting themes and patterns in real-time. When the user mentions something that connects to an earlier response, the Analyst notices.

The Probe Coach identifies opportunities to dig deeper that the Director might miss. “They mentioned their father's business, that might be relevant. Consider following up.”

The Engagement Monitor reads energy and resistance, flags when the interview drifts or the user seems confused or disengaged.

The Scribe documents everything, key quotes, timestamps, summaries, so nothing important gets lost.

They all receive the same inputs, process in parallel, true parallelism through Elixir's BEAM virtual machine, not fake sequential “multi-agent” frameworks that process one at a time, and their observations feed back to the Director for final decisions.

The user experiences a simple chat with a skilled interviewer. They have no idea there's a production studio running behind the scenes. The complexity is invisible; the quality is evident.

This same architecture, concurrent observers processing a shared stream, powers three products I'm building: a brand conversation system, an MCode motivation assessment, and a tutoring platform. Same pattern, different specialists. The architecture is reusable; the agents are swappable.

A Two-Model Architecture for Voice Assessment

YourVoiceProfile.com runs conversational assessments. The architecture uses two models, but the power isn't in which models. It's in when each does its work.

Claude does the hard thinking at design time. Before any user conversation, Claude creates the intelligence artifacts:

- Conversation playbooks defining the complete flow, what to ask, in what order, how to handle different response types, what constitutes a complete answer

- Question banks decomposing the assessment into atomic questions, each with extraction schemas defining exactly what structured data to pull

- Validation checklists specifying what completeness looks like, what consistency means, what quality requires

- Escalation rules defining precisely when runtime complexity exceeds what the simpler model can handle

This is where intelligence lives. Not in the model. In the context files. The expensive thinking happens at design time, encoded into artifacts that any model can follow.

Scout does the fast execution at runtime. Llama 4 Scout handles 80% of user interactions, running conversations, asking questions, extracting structured data. Fast and cheap. It works because the hard thinking is already done. Scout isn't doing deep reasoning. It's following playbooks, matching patterns, extracting data against schemas.

Claude only enters at runtime for genuine edge cases. Low confidence scores. Response patterns that don't match expectations. Synthesis that requires deeper reasoning than pattern matching.

The question isn't “which model is smarter?” It's “have we invested enough in design-time intelligence that runtime can be simple?”

This inverts how most people think about AI architecture. They assume you need the best model for every interaction. The truth is you need the best model for design, and then the fastest model can handle execution, if you've done the design work.

The takeaway: The expensive thinking happens once. The cheap execution happens thousands of times.

The Path Forward

Here's what I've learned: the tools will keep changing. New models every few months. New interfaces. New capabilities. The guide you read today will be outdated by summer.

But the levels don't change.

Level 1: The Collaborator Mindset. Stop asking “which app?” Start asking “what relationship?”

Level 2: Compounding Assets. Skills, frameworks, specifications, memory. Things that make session 100 more powerful than session 1.

Level 3: The Operating Agreements. Decision authority, human-in-the-loop points, visible reasoning, quality standards. Write them down.

Level 4: Production-Grade Systems. Multi-stage pipelines, multi-agent architectures, multi-model designs. AI work that looks like engineering.

Each level builds on the ones before it. You can't design meaningful operating agreements (Level 3) until you have assets worth governing (Level 2). You can't build sophisticated architectures (Level 4) until you have clear agreements about how the pieces work together (Level 3). And none of it works until you've made the fundamental shift from tool thinking to collaborator thinking (Level 1).

The progression isn't optional. Skip a level and the later ones collapse. Try to build a sophisticated multi-agent system without operating agreements, and you'll get chaos. Try to define operating agreements without compounding assets, and you'll have nothing to govern. Try to build assets without the collaborator mindset, and you'll produce elaborate prompts instead of systems.

If you're advising organizations on AI, if you're training people to lead AI initiatives, if you're building an AI strategy, this progression is what matters. Not which chatbot to use. Not the feature list of the latest model. The levels.

The executives struggling with AI aren't struggling because they picked the wrong tools. They're struggling because they're stuck at Level 1. They see AI as a search engine with better sentences, or an automation engine to reduce headcount, or a magic box that produces outputs from inputs.

The executives who thrive have moved through the levels. They see AI as a thinking partner. They build systems, not queries. They externalize expertise into reusable assets. They define clear operating agreements. They architect for sophistication.

You don't need to reach Level 4 tomorrow. But you do need to know what level you're at today, and what it would take to advance to the next one.

The path is open. The levels are clear.

Most AI guides teach you tools. Now you know the levels.

Where are you? And what would it take to advance?